Water's No Man's Land Explained: The Two-Liquid Secret

Water is the most studied molecule on Earth. It covers 70% of our planet, makes up 60% of our bodies, and sustains all life as we know it.

And yet, until recently, scientists couldn't observe what happens to liquid water across a 144-degree Fahrenheit temperature range.

That forbidden zone, called water's "no man's land", is where supercooled water transforms into ice faster than you can blink. It's also where water's deepest secrets have been hiding for over four decades.

In 2023, researchers at EPFL in Switzerland finally cracked it open. What they found could change how we preserve human organs, predict weather, and search for alien life.

Water’s Bermuda Triangle (this gets geeky, but stay with me)

Between -40°F and -184°F (-40°C to -120°C), liquid water essentially refuses to exist long enough for scientists to study it.

This temperature range is called "no man's land", a term coined by researchers frustrated by their inability to observe supercooled water in this zone.

The problem? Ice crystallization gets progressively faster as temperature drops. At -54°F (-48°C), right in the heart of no man's land, water transitions from liquid to solid in microseconds. Millionths of a second.

It's like trying to photograph a soap bubble at the exact instant it pops.

For 40 years, this made no man's land completely inaccessible to direct observation. Scientists could study water above -40°F. They could study amorphous ice (frozen water with a glass-like structure) below -184°F.

But that middle zone? A complete blind spot in our understanding of the most important molecule on Earth.

Why Water Behaves So Strangely

Here's the thing about water: it breaks almost every rule that other liquids follow.

Most liquids get denser as they cool. Water does too, until it hits 39°F (4°C). Then it reverses course and becomes less dense as it continues cooling. This is why ice floats, why fish survive in frozen lakes, and why Earth didn't turn into a lifeless ice ball billions of years ago.

Most liquids become less compressible when cold. Water becomes more compressible when supercooled below 32°F (0°C).

Scientists have documented over 70 of these "anomalous properties", behaviors where water defies the rules that govern virtually every other liquid on the planet.

The leading theory to explain these water anomalies? It sounds almost absurd:

Water is actually two different liquids pretending to be one.

The Two-Liquid Theory: Low-Density and High-Density Water

At the molecular level, water exists as two distinct structural personalities:

Low-Density Liquid (LDL): An open, tetrahedral structure where water molecules arrange themselves like ice that hasn't fully committed. Each H₂O molecule bonds to exactly four neighbors in a pyramid-like pattern through hydrogen bonding.

High-Density Liquid (HDL): A compact, disordered structure. This form actually behaves like a "normal" liquid.

Snapshot of a molecular dynamics simulation of supercooled water. Credit: F. Sciortino et al

At room temperature, these two forms are so well-mixed you can't tell them apart. Your glass of water is secretly both types, coexisting like roommates who get along perfectly.

But cool water below 32°F, into the supercooled zone where it stays liquid despite being below freezing point, and these molecular roommates start separating. They want different spaces.

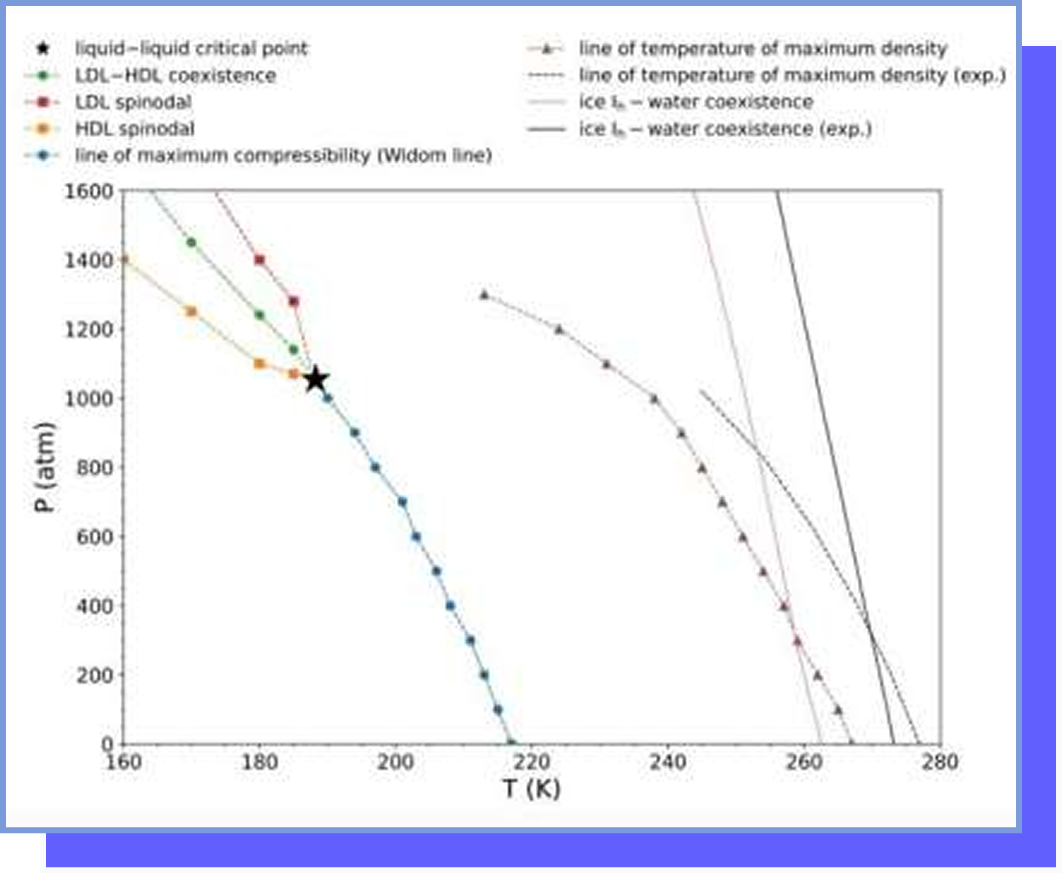

Around -53°F (-47°C), water hits what scientists call a liquid-liquid critical point.

Think of it like oil and water separating into distinct layers. Except in this case, both layers are water. Just... different structural forms of water.

Phase diagram of supercooled water predicted by molecular dynamics simulations with the DNN@MB-pol potential. Credit: F. Sciortino et al

If scientists could observe this critical point directly, it would explain water's entire "personality disorder", all 70+ anomalous properties in one unified theory.

There's just one problem: water freezes too damn fast in that temperature range to watch the liquid-liquid phase transition happen.

The Molecular Runaway Train

Let me explain what's happening at the molecular level when water crystallizes in no man's land.

At -40°F, ultra-pure water, no dust particles, no container walls, nothing to trigger ice nucleation, stays liquid for maybe a few seconds.

At -58°F? Microseconds.

At -76°F? You blink, and it's ice.

As supercooled water cools further, molecules start arranging themselves into four-coordinated tetrahedral structures. Each H₂O bonds to exactly four neighbors in the same geometry found in ice crystals.

Call them "pre-ice" molecules. They're dominoes standing on edge, one nudge from locking into solid crystalline form.

The colder it gets, the more pre-ice molecules form. And the more you have, the faster they all cascade into crystallization. One goes, they all go, in a chain reaction that happens faster than any instrument could measure.

By -54°F, ice crystal formation hits maximum speed. Water molecules freeze before they can even settle into their liquid positions.

This is why no man's land remained completely inaccessible for four decades.

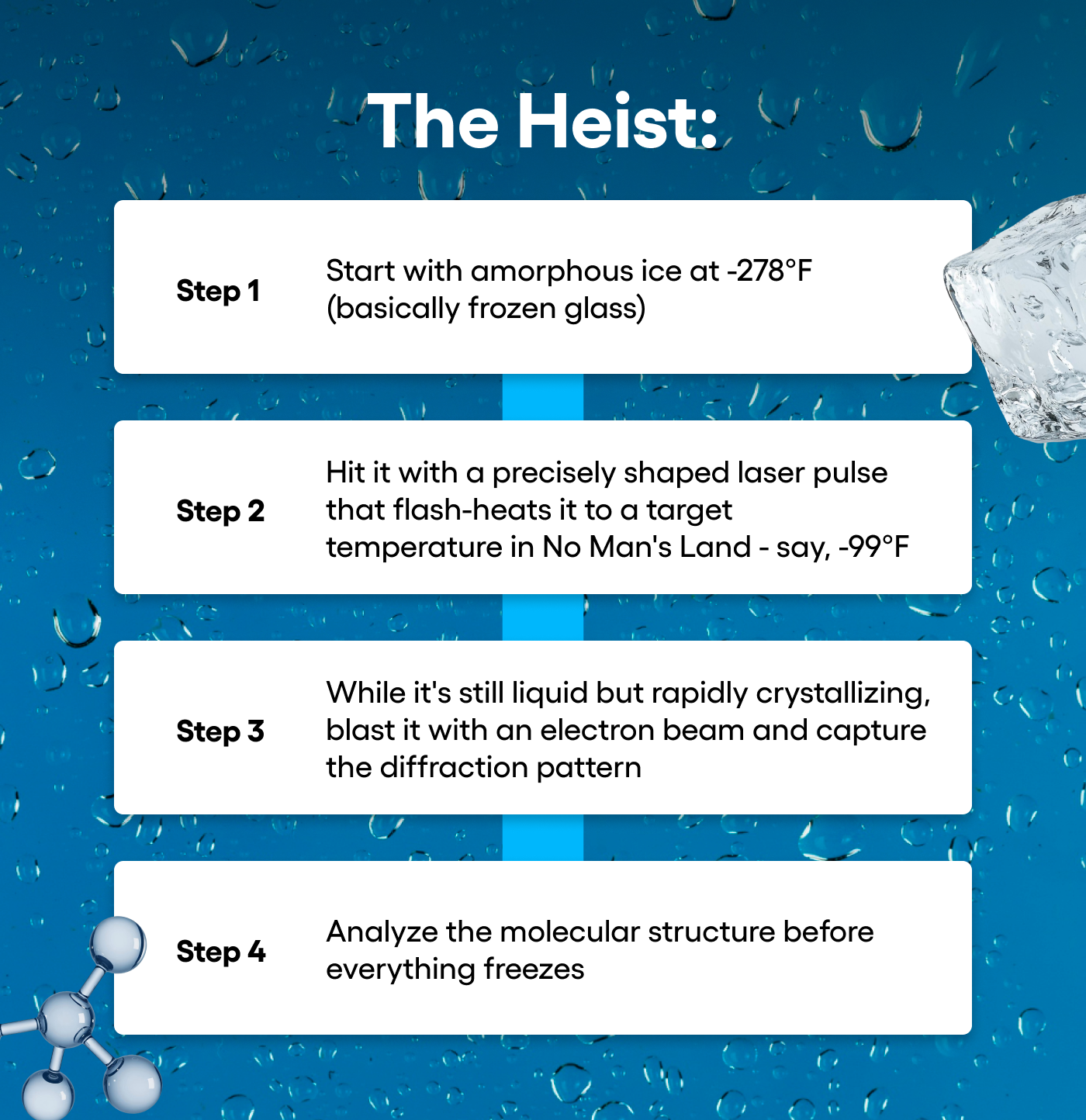

The Scientific Heist: 6 Microseconds to Catch Water's Secret

In 2023, a team at EPFL pulled off what amounts to a scientific heist.

They couldn't keep supercooled water liquid long enough to study it. So they asked a different question: What if we only need it liquid for 6 microseconds?

The entire measurement window was 6 microseconds. That's 0.000006 seconds.

Fast enough to photograph supercooled water before ice crystal formation ruins everything.

They repeated this experiment at dozens of different temperatures across no man's land, building the first complete map of water's structure from room temperature all the way down to cryogenic conditions.

What They Discovered About Supercooled Water

The results surprised everyone.

Water's structure evolves smoothly as it cools. Like a gradual transformation rather than an abrupt switch.

By -99°F (-73°C), liquid water is structurally almost identical to amorphous ice, a form of frozen water where molecules are in a disordered state, unlike the orderly crystalline ice we're familiar with. But it's still technically liquid: the molecules can still move around, just barely.

This doesn't disprove the two-liquid theory. It just means the liquid-liquid critical point is occurring under slightly different conditions than originally predicted.

Follow-up studies in 2024-2025 using machine learning simulations pinpointed exactly where water's two personalities split:

Temperature: -63°F to -33°F (-53°C to -36°C)

Pressure: 1,900 to 25,000 psi (for context, normal atmospheric pressure is about 15 psi)

And here's the kicker: that temperature range is exactly where ice crystallization happens fastest.

Water's trying to separate into high-density and low-density liquids, but ice keeps interrupting like an overeager photobomber.

Francesco Paesani, a computational chemist at UC San Diego, ran molecular simulations so realistic he said "you can almost drink it."

His team watched water molecules at the critical point flickering between high-density liquid and low-density liquid structures faster than any instrument can measure directly.

One study using ultrafast X-ray lasers showed the liquid-liquid transition itself happens in less than 100 nanoseconds, with ice crystallization kicking in around 1 microsecond later.

That's a 900-nanosecond window, less than one-thousandth of the 6 microseconds the EPFL team used, to catch water's two structural personalities splitting apart.

Just 900 nanoseconds to observe arguably one of the most fundamental transitions in nature.

That's why it took 40 years to crack this.

Why Understanding Supercooled Water Matters

Understanding no man's land has real-world applications that could save lives and answer some of humanity's biggest questions.

Cryopreservation: Freezing Human Organs Without Destroying Them

Organ cryopreservation, freezing organs for transplant, is currently limited by ice crystal formation. When water inside cells freezes, those crystals act like tiny knives, shredding cell membranes and destroying tissue architecture.

This is why we can't bank organs the way we bank blood. Donated kidneys, livers, and hearts must be transplanted within hours, creating enormous logistical challenges and geographic inequities.

Vitrification, turning organs into a glass-like solid state without ice crystals, offers a potential solution. If we understand exactly when and how water crystallizes at the molecular level in no man's land, we can develop better techniques to achieve vitrification in larger organs.

There are over 100,000 people on organ transplant waiting lists in the US right now. Better preservation through understanding supercooled water crystallization could save thousands of lives by extending organ viability and enabling organ banking.

Climate Models: Actually Predicting Weather Correctly

Supercooled water droplets exist naturally in clouds at temperatures from 32°F down to -40°F.

Their behavior, whether they stay liquid or freeze into ice crystals, determines whether you get rain or snow, whether a storm intensifies or fizzles out.

Here's the problem: climate models cannot simulate clouds correctly without understanding how supercooled water behaves.

Cloud formation involving supercooled water droplets is one of the largest sources of uncertainty in climate projections. This research on water's no man's land helps close that gap, potentially improving weather prediction and climate modeling significantly.

The Search for Alien Life: Europa and Enceladus

Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus both have confirmed liquid water oceans beneath miles of ice.

Those subsurface oceans exist at temperatures well below 32°F, right in the supercooled range that scientists just mapped for the first time.

Understanding how water behaves under these extreme conditions helps scientists predict what's happening beneath those ice shells. Including whether the conditions could support microbial life.

Are there alien organisms swimming around in Europa's subsurface ocean right now?

We won't know until we get there. But understanding supercooled water gets us one step closer to knowing what to look for.

Not bad for 6 microseconds of work.

Frequently Asked Questions About Supercooled Water

What is supercooled water?

Supercooled water is liquid water that remains in a liquid state below its normal freezing point of 32°F (0°C). This happens when water is extremely pure and there are no nucleation sites (like dust particles or container imperfections) to trigger ice crystal formation. Supercooled water can exist down to about -40°F (-40°C) under normal conditions, though it becomes increasingly unstable at lower temperatures.

Why does ice float on water?

Ice floats because water exhibits an anomalous density behavior, it becomes less dense as it freezes, unlike almost every other liquid. This happens because the hydrogen bonding between water molecules forces them into a tetrahedral crystal structure that takes up more space than the disordered liquid arrangement. This unique property is what prevents lakes and oceans from freezing solid from the bottom up, allowing aquatic life to survive winter.

What is water's "no man's land"?

Water's no man's land is the temperature zone between approximately -40°F and -184°F (-40°C to -120°C) where liquid water crystallizes into ice so rapidly that scientists couldn't study it directly until 2023. In this zone, the ice crystallization rate is so fast that water transforms from liquid to solid in microseconds, too quick for traditional observation methods. This zone is critical for understanding water's anomalous properties.

Can water really exist as two different liquids?

According to the liquid-liquid phase transition theory, yes. At the molecular level, water can exist as two distinct structural forms: a low-density liquid with an open tetrahedral structure (similar to ice), and a high-density liquid with a compact, disordered structure. At room temperature, these forms are completely mixed. But at supercooled temperatures and high pressures, they can separate, similar to how oil and water separate into distinct layers.

How does supercooled water research affect organ transplantation?

Understanding supercooled water and ice crystallization could revolutionize organ cryopreservation. Currently, ice crystal formation during freezing destroys cell membranes and organ tissue, limiting how long donated organs can be preserved. By understanding exactly how and when water crystallizes in the no man's land temperature zone, scientists can develop better vitrification techniques, cooling organs to glass-like states without ice formation, potentially enabling long-term organ banking and saving thousands of lives on transplant waiting lists.

Water World Roundup

1) AI "Ecobot" cleans up lakes and rivers in Singapore

Credit: Shutterstock

Credit: Shutterstock

Credit: CNBC

Water Meme of the Month

Meme inspired by X (Formerly Twitter) handle Marvel Core